Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 801

A Grammar of Bisaya in Davao

Mary Jane A. Cooke

University of Mindanao

Ana Helena R. Lovitos, PhD, MedStud

University of Mindanao

Abstract:- This research presents a detailed linguistic

description of the Bisaya in Davao language based on the

examination of Basic Linguistic Theory. Three primary

language consultants are native speakers of the language

who translated and recorded word and sentence lists for

accurate pronunciation. The analysis reveals the

language's phonological, morphological, syntactic, and

morphosyntactic characteristics. Based on the translated

eliciting materials spoken and pronounced by the

language consultants, there are three vowels and sixteen

consonants in the phonemic inventory. Distinct

phonological characteristics such as minimal pairs,

diphthongs, and phonotactics are readily apparent. It

demonstrates that the language has morphological

characteristics and follows ergative-absolutive and verb

Initial structure, precisely like other Austronesian

languages in the Philippines. This description provides

actual language documentation, additional research on

language contact or migration, linguistic typology, and

crosslinguistic study. This is vital for students and

teachers in DepEd Davao in teaching the Bisaya in

Davao as a mother tongue.

Keywords:- Applied Linguistics; Bisaya, Language

Description; Linguistic Features; Philippines.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Cebuano (ISO 639-3 ceb) language belongs to the

"Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Greater Central

Philippine, Central Philippine, Bisayan, Cebuano,

Mansakan, Davaweño. It is extensively spoken in the Bicol

region, including parts of Mindanao and the Visayas

(Ethnologue, 2021). Although the Expanded Graded

Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIS) (Simons &

Fennig, 2022) considers the language to be institutional, that

is, it has been developed to the point and is used and

sustained by institutions beyond the home and community;

the language still needs to be documented to add to the

language's sustainable and functional literature.

In her study, Rubrico (2012) defined Cebuano,

referred to as Bisaya or Binisaya by the people of Davao, as

the language most people speak. In addition, she cited

Ethnologue (2009), one in every three (33.32%) is Cebuano.

The regional quarterly publication of the Davao NCSO

gives the following ethnolinguistic groups distribution in

Davao: Cebuano, 74.56%; Tagalog, 3.86%; Hiligaynon,

3.43%; Bagobo, Guiangao, 3.16%; Davaweño, 1.26%;

Tagacaolo, 2.38%; Bilaan, 1.67%; Ilocano, 1.01%; Waray,

0.55%; Manobo, 2.15%; Maguindanao, 1.91%; Mandaya,

2.01%; other languages, 2.04%; uncertain, 0.01%.5

According to Ethnologue 2009, Davawenyo synthesizes

Filipino, Cebuano, and other Visayan dialects. In addition,

Lobel and Pouezevara (2021) added that the only Philippine

language with a native speaker population that approaches

Tagalog (16 million) is Cebuano. Additionally, Cebuano,

which is spoken as a native tongue in the central part of the

Philippines, is the only language to match its geographic

range, the majority of central and eastern Mindanao, the

Visayan Islands, and beyond. Compared to Tagalog as the

most extensively studied language among the various

academic studies on the Philippine languages, as claimed by

Jubilado (2021), Davao Bisaya is scarce and limited as

studies were focused richly on the Visayas region.

Moreover, it appears to be undocumented throughout

Mindanao, particularly Davao City. Some literature

available on the linguistic analysis of Cebuano is rich and

timely. However, as a result, it is critical to preserve this

Davao variety. Hence, it the important to document this

Davao variety to add to the rich literature of Philippine

languages. Language is an ever-evolving entity it is difficult

to predict when it will change (Atos,2015). Therefore,

language documentation is an essential task for any linguist

and research enthusiast to consider. However, high-quality

data and literature availability are critical for continuing

these investigations. Speakers of all languages must

consciously document their languages so that future

generations can utilize them as guides or references.

The documentation of languages, cultures, and

histories of the world's peoples has been an exciting

undertaking in the past, as Hinton, Leanne, et al. (2018) put

it. She cited epi-Olmec hieroglyphic writing, one of the

many writing systems developed in Mesoamerica and used

thousands of years ago. Besides, the works of Campbell,

L.& Rogers, C. (2015) and (Klessa, 2014) made a brief

review of the history of linguistic ideas shows. It intensified

that language documentation is among the oldest traditions

in the linguistic field.

New literature, such as grammar, would be a great

addition. While it is true that this language is thriving and

valuable in some pillars of society, it is still undeniable that

it will be a rich addition to the teaching of the mother tongue

under DepEd's Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual

Education (MTBLE) to uphold its Four Minima for a

language to become a mother tongue: weaving to standard

orthography, grammar, dictionary, and literacy materials. In

this case, this study would address the grammar requisite.

Suffice it to say that this endeavor of the Grammar of Bisaya

in Davao is significant.

It is for this cause that this proposal is postulated.

Writing a Grammar involves two primary objectives:

documentation of threatened or endangered languages and

Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 802

(making these languages mother tongues. Documentation

includes a detailed description of the language's

phonological, morphological, and syntactic aspects.

II. METHOD

The research design of this paper is qualitative

descriptive research, specifically descriptive which explores

the documentary analysis and involves gathering data

through comprehensive interviews from the selected three

informants who are Bisaya native speakers. The research

participants or language consultants were three Davao

Bisaya, native speakers in Davao City. Before data

collection started, I prepared the elicitation materials, which

are the 505 Wordlist and 700-sentence list from the

University of the Philippines Linguistics Department, within

the parameters of my research study. Experts validated the

elicitation materials to ensure the viability of the expected

output. The language consultants of this study were three

participants who were native speakers of the language. They

are more than 20 years old. They were educated enough to

translate from their native language to Bisaya and Tagalog.

Barlow (2020) noted that people older than 30 tended

to be fluent speakers (of varying proficiency). In contrast,

people in their twenties only seemed capable of producing

basic phrases (although their comprehension might have

been quite good). The translation was conducted in the

comfort of their preferred location during their free time.

For further clarification and validation of the elicited data,

these respondents were interviewed in person and via

Facebook messenger.

To gather sufficient data for this study, I used the

elicitation technique to collect the data for this study. I

utilized the elicitation materials, such as the 505-Word List

and the 775-Sentence List designed and enhanced by the

linguistics department of the University of the Philippines

(Diliman) (UP Department of Linguistics, 2018a, 2018b,

2018c). The elicitation materials were used with appropriate

consent from the rightful owner. The first three materials

enumerated above are all wordlists, which have been

utilized to collect lexical data from the Bisaya language to

decide how to test the emerging conclusions.

This study was conducted with a firm adherence to the

ethical protocols. The researcher religiously requested and

secured from key school officials the corresponding

permission necessary to complete this research.

Furthermore, the researcher ensured the appropriateness of

identified recruiting parties and reviewed the risks and

measures to mitigate these risks (including physical,

psychological, and social-economic. Proper authorization

and consent are also obtained from the sample of the study,

in which they are assured that all their rights would be fully

protected, specifically in handling the data such as, but not

limited to, voluntary participation, privacy, and

confidentiality, informed consent process, recruitment,

benefits, plagiarism, fabrication, falsification, conflict of

interest (COI, deceit, permission from organization/location:

Technology Issues and authorship.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

With roughly 16 million native speakers, Cebuano is

the only language spoken in the Philippines, close to

Tagalog's native speaker population. Moreover, speaking as

a native tongue in the central region of the Philippines,

Cebuano is the only language to match its geographic

breadth—the majority of central and eastern Mindanao, the

Visayan Islands, and beyond.

The Place where the Language is Spoken

Bisaya or Binisaya is a variety of the Cebuano (ISO

639-3 ceb) language. It belongs to the "Austronesian,

Malayo-Polynesian, Greater Central Philippine, Central

Philippine, Bisayan, Cebuano, Mansakan, Davaweño.

Widely spoken in the Bicol region: south Masbate province;

parts of Mindanao; throughout the Visayas regions

(Ethnologue, 2021). Cebuano is classified as ISO 639-3 ceb,

a member of the "Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Greater

Central Philippine, Central Philippine, Bisayan, Cebuano,

Mansakan, and Davaweño" ethnic groups. The Philippine

language is widely spoken in the Bicol region, including

south Masbate province, sections of Mindanao, and the

Visayas. It is natively called by its generic term Bisaya or

Binisaya.

Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 803

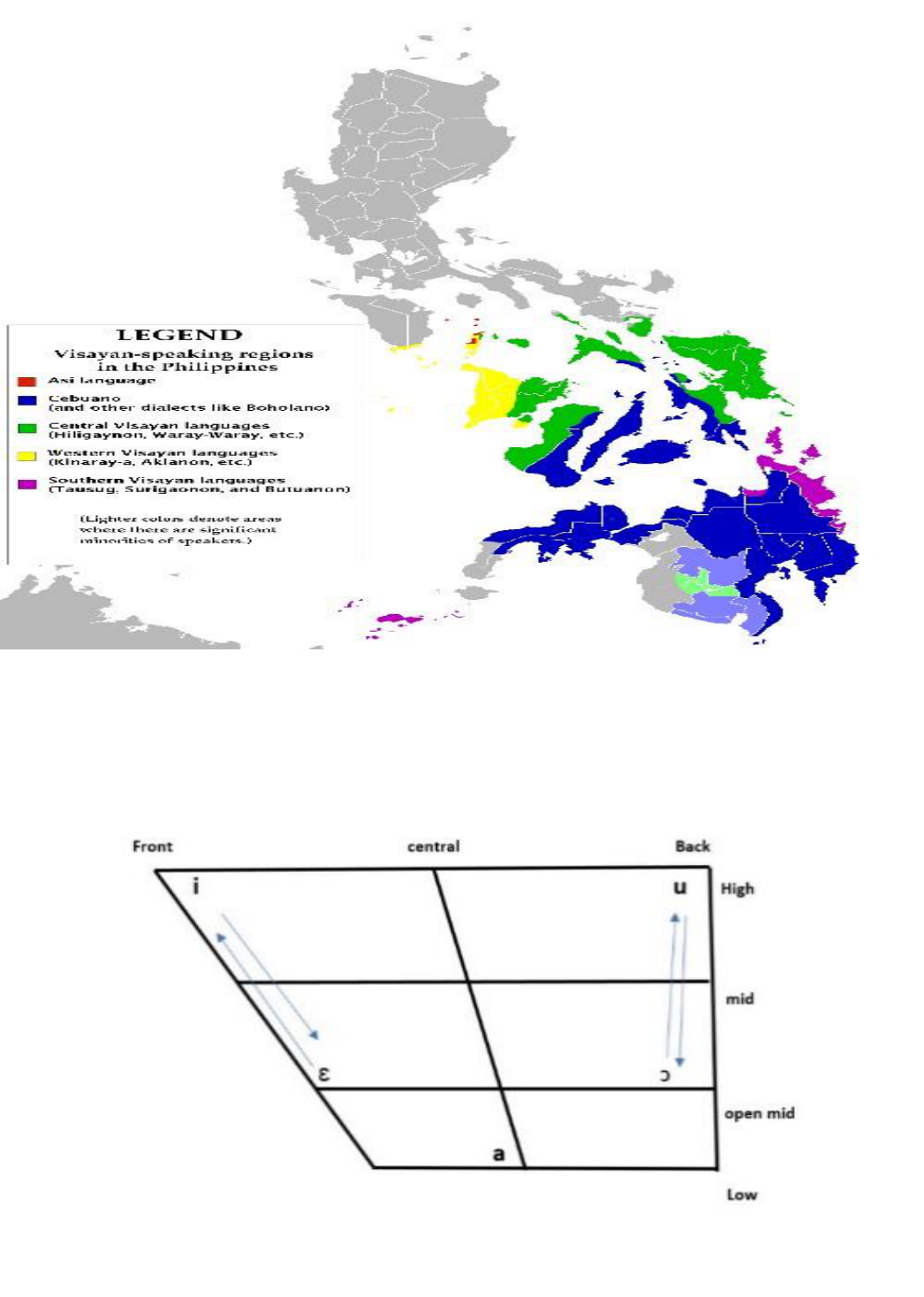

Fig 1 Visayan Language Distribution Map

Source: Https://Commons.Wikimedia.Org

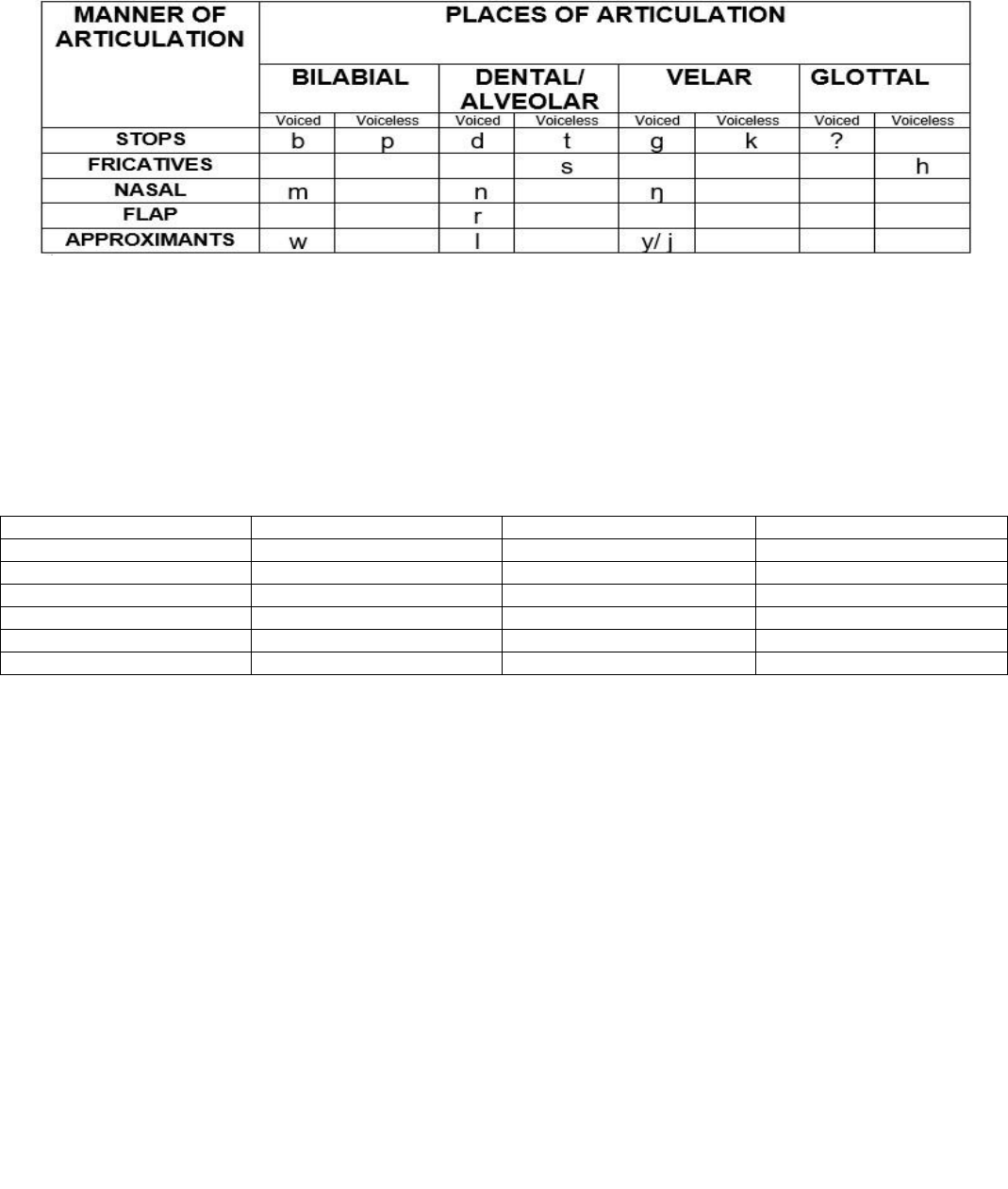

Bisaya in Davao Phonological Component

The Bisaya's phonological structure in Davao comprises the phonemic inventory of vowels and consonants, phonotactics,

which addresses the restrictions on phoneme combination, and phonological constraints, which address Bisaya in Davao

consonant clusters, and the observable phonological processes employed to simplify their speech.

Fig 2 The Davao Bisaya Vowels

Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 804

Based on the translated eliciting materials spoken and

pronounced by the language consultants, Bisaya in Davao

vowels and consonants are applied to Bisaya in Davao's

sound system, as in all other Philippine languages. Three

sounds—/a/,/i/, and /o/u/—are the critical discoveries for

vowels. They could be in diphthongs, minimal pairings, and

open and closed syllables. Consonants consist of 16 sounds,

including /b/, /d/, /g/, /k/, /h/, /l/, /m/, /n/,/p/, /r/, /s/, /t/, w/,

/y/j/, and / ʔ/ (Refer to Table 1). They are divided into four

groups based on how they are articulated: stops, fricatives,

nasals, flaps, and approximants. Also, the consonants are

categorized in their places of articulation based on the

tongue positions; bilabial, dental/alveolar, velar, and glottal.

Table 1 The Bisaya in Davao Consonant Phonemes

Bisaya In Davao Morphological Features

Although Bisaya in Davao is simpler than other Philippine languages, it is ideal to be aware of the slight complexity of the

morphological process. Morphological awareness is fundamental because, according to Borleffs et al. (2019), in the study of

Lobel and Pouezevara (2021), after mastering basic decoding, morphological awareness continues to be a crucial skill for reading

development in higher grades. In some languages, it is also connected with the capacity to read words. Morphemes are the

primary/smallest unit of language that bares meaning. These morphemes are also observed in the Bisaya in Davao variety. Some

of which are inflectional, derivational, and free. Inflected words retain their lexical categories. The affixes added to the root word

add information or grammatical functions needed by the word, such as tense, case, number, and agreement to other words. The

Bisaya in Davao verbs demonstrate this morphological process (Refer to Table 2).

Table 2 Bisaya in Davao Inflected Words

Root Words

English

Inflected Words

English

tindog

stand up

nitindog

stood up

motindog

will stand up

tanom

plant

nitanom

planted

motanom

will plant

tao

person

mga tao

persons

balay

house

mga balay

houses

Bisaya in Davao root words changed forms in the

above examples through the affixes attached, but their

lexical categories remained unchanged. For example, the

verb tindog stand up changed the form to nitindog stood up

by adding the prefix ni became a contemplative form of a

verb, which denotes that the action has already been

completed. In the same manner, adding the prefix mo- to the

word will make it an imperfective tense of the verb;

transforming it to motindog will stand up, thus making it an

action still to be completed at some point in the future. This

is also true for the verb tanom plant, respectively. As a

result, the affixes added to Bisaya in Davao root words

provide additional information or grammatical structure.

Tindog and tanom, two root words used in the examples,

are verbs. No matter what affixes are added, they still

function as verbs in that sense; the only difference is

between their contemplative and imperfective tenses. The

plurality in Bisaya in Davao is expressed periphrastically

expressed through mga. The root words, tao person and

balay house are singular nouns. When the plural marker

mga precedes them, they become plural, mga tao persons;

mga balay houses but remain a noun as their lexical

category. In this case, the number changes, but not their

lexical category. Inflectional morpheme combinations do

not form new words. Delahunty, G. P., & Garvey, J. J.

(2004) added that they merely alter the word in which they

appear to denote grammatical features like plurality.

The Syntax in Bisaya in Davao

Languages require more than simply stringing words

together to form whole sentences. To create a notion, certain

words must be joined together, and groupings of words must

be grouped to produce a thought. These groupings are

controlled by rules, or what is known as syntax. Each

language has syntax, which means that syntax is universal.

However, the syntax is also language-bound, meaning that a

language's syntax may be like or different from other

languages. The sequence of words is essential for

comprehending sentences in languages because each

language has its distinctive sentence structure and word

Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 805

order. The Bisaya in Davao exhibits characteristics of being

an Ergative - Absolutive language and a Verb Initial

language, just like other Austronesian languages in the

Philippines. The presentation of the language analysis

covers sentence patterns as well as phrase and clause

structure. Traditional grammatical analysis presents an

immediate distinction between intransitive and transitive

verbs.

In contrast to intransitive verbs, transitive verbs take

objects or a patient. In Bisaya in Davao, several transitive

and intransitive constructions are shown. The number of

necessary noun arguments a verb can take in a grammatical

formulation depends on its transitivity.

The verb has a big role in Bisaya in Davao and other

languages. How many nouns are required to build the phrase

depends on the verb. This idea of transitivity is akin to

valency, which also encompasses nouns other than the one

the verb directly affects. Intransitive construction contains

just one distinct argument, like all other languages: the

subject. The absence of an object renders the statement

comprehensive and comprehensible but lacking essential

details. This construction has also been made evident by the

Bisaya in Davao transitive construction.

Verb Initial Sentences in Bisaya in Davao

The verb initial patterns in Philippine languages are

vital to sentence formation. Predicate occurs first, then the

subject of the sentence, a pattern also seen in Austronesian

languages. In both spoken and written language, this

arrangement comes naturally. Although additional

languages, such as Tagalog, may allow the inverse order, the

natural and straightforward way of constructing sentences in

these languages, including Bisaya in Davao, is verb first,

followed by the arguments.

The Morphosyntax in Bisaya in Davao

The markers are one of the most observable features of

Philippine languages categorized as Austronesian. These are

words that do not have language equivalence in other

languages. They do not have an accurate literal translation.

Their primary purpose is syntactic. The sentences may have

all the main parts, verbs, and nouns but would still sound

awkward and complete with these markers. The discussion

above shows that these markers are also found in Bisaya in

Davao sample sentences. The markers are one of the most

distinguishing characteristics of Austronesian-classified

Philippine languages. These terms do not exist in other

languages in the same way. They are not translated literally

and accurately. Their primary objective is syntactic. Even

though the sentences contain all the necessary nouns and

verbs, they would sound odd and unfinished without these

markers.

The Verbal Affixation and Case Marker in Bisaya in

Davao

As previously mentioned, the co-indexing of the absolutive

markers to the affixation of the verb in the sentence is a very

noticeable morphosyntactic trait of Austronesian languages

spoken in the Philippines. This characteristic is typically

seen in Bisaya in Davao as well. Depending on the verbal

affixation, the "ang," the absolutive marker in Bisaya in

Davao, adopts a different voice or emphasizes a particular

aspect. The aspects of a verb in a sentence are altered by

changing its affixes, as is the verb's necessity for the

absolutive case to take on voice. Like other Philippine

languages classified as Austronesian languages, Bisaya in

Davao contains a trait known as verbal affixation related to

its arguments in sentences. These languages may be studied

well using this morphosyntactic feature, which also provides

a very understandable description of the typology of the

languages.

IV. CONCLUSION

The extensive discussion on the widely spoken Bisaya

in Davao, a Cebuano variety, demonstrated the relevance of

the need to document this. This research offers a linguistic

description of the language's grammar based on an

evaluation of Basic Linguistic Theory and strict adherence

to the functional theory of grammar in assessing the

language's peculiarities. The study identified the

phonological, morphological, syntactic, and

morphosyntactic features of the language with the assistance

of the three principal language consultants (of varying ages),

who are native speakers of the language and diligently

translated and recorded word and sentence lists for accurate

pronunciation. Despite Bisaya in Davao's relative simplicity

compared to other Philippine languages, it is advisable to be

aware of the language's morphological system's slight

complexity. It illustrates an intriguing set of morphological

traits from which morphemes can derive or inflect.

Language's morphological procedures and the existence of

the lexical categories of prefixes, infixes, and circumfixes

are excellent sources for linguists to study further and

investigate.

They are also a valuable resource for MTBLE teachers

in their instruction and a source of knowledge for Bisayan

speakers in Davao to learn. This description paves the way

for future researchers on actual documentation of the

language and pursues research topics like dialectal

distinctions in Visayas and Mindanao, language contact,

survival of the language despite the presence of other

prominent and dominant languages, language migration,

linguistic typology, and even crosslinguistic study. I hope

other linguist enthusiasts will continue what this paper may

not have comprehensively addressed in some areas and may

have overlooked some significant works expected

discussions. This significant undertaking may provide a

concrete reference for Mother Tongue–Based Multilingual

Education (MTB-MLE) for students and teachers in DepEd

divisions in Davao. As a result, the teaching of Bisaya is a

mother tongue because it introduces linguistic notions that

support pedagogical strategies and resources. Furthermore,

this humble research endeavor hopes to strengthen the

community's awareness of preserving languages regardless

of their status through language documentation in

partnership with the National Commission on Indigenous

Peoples (NCIP).

Volume 8, Issue 2, February – 2023 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology

ISSN No:-2456-2165

IJISRT23FEB832 www.ijisrt.com 806

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our

family, friends, colleagues, students, immediate supervisors,

and language consultants for their love and support.

About the Authors

Mary Jane A. Cooke graduated BSEd Major in

English and MAed in English Language Teaching. She

is currently working on her Ph.D. in Applied

Linguistics dissertation at the University of Mindanao.

She is also currently teaching at the Philippine College

of Technology and the University of Southeastern

Philippines.

Dr. Ana Helena R. Lovitos is a seasoned Language

Professor at UM Davao. A graduate with a BSEd

Degree in English, Master of Arts in Language

Teaching (MALT), and PhD in Applied Linguistics.

She completed her Master of Educational Studies

(MedStud) in Educational Research at the University of

Newcastle, Australia.

REFERENCES

[1]. Atos, E. G., et al. (2015)."A Grammatical Sketch of

Hinigakit."

[2]. Barlow, R. (2020). A sketch grammar of Pondi. ANU

Press.

[3]. Eberhard, D.M.,Fennig, C.D, & Simons(2022).

Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-fifth

edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

[4]. Retrieved from: http://www.ethnologue.com.

[5]. Hinton, L., Huss, L. M., & Roche, G. (Eds.).

(2018). The Routledge handbook of language

revitalization (p. 1). New York: Routledge.

[6]. Jubilado, R. (2021). Comparative Ergative and

Accusative Structures in Three Philippine

Languages. Southeastern Philippines Journal of

Research and Development, 26(1), 1–18.

[7]. Justeson, J. S., & Kaufman, T. (1993). A

decipherment of Epi-Olmec hieroglyphic

writing. Science, 259(5102), 1703-1711.

[8]. Klessa, K., & Nau, N. (2014). Compilation of

Language Resources and On-Line Dissemination of

Knowledge about Endangered Languages and

Linguistic Heritage. In Human Language

Technologies–The Baltic Perspective (pp. 192–195).

IOS Press.

[9]. Lobel, J. and Pouezevara, S. (2021). Characteristics

of Select Philippine Mother Tongue Languages Used

in Basic Education Teaching and

Learninghttps://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00XBQ5.

pdf

[10]. Rogers, C., & Campbell, L. (2015). Endangered

languages. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of

Linguistics.

[11]. Rubrico, J. G. U. (2012). Indigenization of Filipino:

The case of the Davao City variety. Kuala Lumpur:

University of Malaya.

[12]. (2018a). The Revised 615-Word List. Quezon City,

PH: Department of Linguistics, University of the

Philippines

[13]. (2018b). A 505-Word List. Quezon City, PH:

Department of Linguistics, University of the

Philippines

[14]. (2018d). The 775-Sentence List. Quezon City, PH:

Department of Linguistics, University of the

Philippines.